The famous Australian comedian and author Barry Humphries once said - snidely - that if you include Marilyn Monroe in a stage play in Sydney, you’re sure to have a success. The much-esteemed Polish Drama Theatre of Sydney, Fantazja, seems to have followed this advice in its recent first English-language production, The Trial Of Dali.

Fantazja, formed in 2002 and sustained by a passionate commitment from its directors and actors, has a formidable record of Polish-language theatre productions in Sydney and at cultural festivals in other Australian capitals. The company is made up of both amateurs and highly-trained professionals. It’s been a great boon to the Polish community, who have brought from their homeland an old and deep theatrical inheritance which Australians can only envy.

For its first English-language play venture, under Artistic Director Joanna Borkowska-Surucic, and thus a courageous step out of its comfort zone, Fantazja has made an intriguing choice. The Trial of Dali is the work of Andrew Kolo, a Pole living in California and writing in English.

I can understand why the company might have shied from any play well-known in the Anglo-American-Australian repertoire, which would have invited a daunting and unfair level of critical comparison. The Trial of Dali ticks some interesting boxes: new, definitely European sensibility at work in it though not of a classical kind, yet fresh, anarchic and American enough to offer something different to an Australian audience.

True to its central character, Trial is in heart and essence a Surreal project. If one asks from it too much logic, too much cohesion, even too much common sense, one is missing its point. The artist comes from New York to be put on trial in his home country of Spain for reasons, and under circumstances, that are never really explained. Andy Warhol and Pablo Picasso, as well as Monroe, make brief and piquant appearances in the proceedings. The trial process itself is a variant of courtroom farce, with hysterical or seductive counsel, a biased judge, and a guard who seems to have strayed in from a Muscle Beach Robot video game.

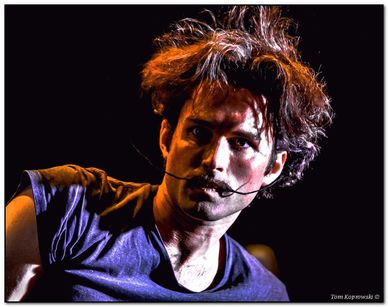

James Domeyko as Dali is an inspired choice, inhabiting the role given him with physical and linguistic brio. The broader Australian stage awaits him. He and Jola Szewczyk, who brings warmth and sympathy to the part of his wife Gala - interestingly of the older, almost maternal figure - create a convincing portrait of a couple truly bound to each other in every circumstance. All the company of ten are keen and enthusiastic.

The Trial wants to take us into the meaning of Dali, and its methods are not linear and analytic. The courtroom shenanigans and unexplained motivations are best understood as a pretext, the ground for a Bergson’s ‘leap’ apprehension of the artist rather than as a quasi-historical account of him and his path of inspirations.

The performance I saw struck me, in some way, as still a work in progress. The moments of choreographed dance, with stark lighting variations and intense movement were brilliant, completely appropriate to the surrealistic potentials of the play. The music track was amusingly outlandish. The set was studded with Dalian small props, through I’d have liked to see more of his distinctive art projected onto the backdrops - as far, of course, as law and copyright allow.

Some of the cast, understandably, may not have been fully at ease in public performance of their adopted language, with its particular rhythmic cues and rhetorical springs; often they communicated an inhibition, not so much of expression, as of timing. Yet what the text seems to be aspiring towards is a zany, madcap animation, a circumvention of reason that is not necessarily assisted by longueurs or slow takes. A future production might consider, not so much a Pinter or even a Beckett treatment but - to borrow further from the classic cinema which is already in part inspiring it - a little more Marx Brothers pace.

Nonetheless the Artistic Director and the company should be congratulated for tackling this unusual and challenging play. When I look at the wonderful list of modern Polish drama (including works by Zapolska, Perzynski, Przybora, Gronski) that Fantazja has produced over the last sixteen years for their Sydney compatriots, I nurse the hope it might look in that direction again, for a wider audience. Might it mount English-translated versions of some of these, often viscerally political, plays? I am sure Sydney theatre-goers would welcome that, a view into a fascinating world they have heard of yet never seen dramatized.

(c) Copyright JOHN STEPHENSON 2018

Author of The Baker’s Alchemy ( A tale of old Poland)

The famous Australian comedian and author Barry Humphries once said - snidely - that if you include Marilyn Monroe in a stage play in Sydney, you’re sure to have a success. The much-esteemed Polish Drama Theatre of Sydney, Fantazja, seems to have followed this advice in its recent first English-language production, The Trial Of Dali.

Fantazja, formed in 2002 and sustained by a passionate commitment from its directors and actors, has a formidable record of Polish-language theatre productions in Sydney and at cultural festivals in other Australian capitals. The company is made up of both amateurs and highly-trained professionals. It’s been a great boon to the Polish community, who have brought from their homeland an old and deep theatrical inheritance which Australians can only envy.

For its first English-language play venture, under Artistic Director Joanna Borkowska-Surucic, and thus a courageous step out of its comfort zone, Fantazja has made an intriguing choice. The Trial of Dali is the work of Andrew Kolo, a Pole living in California and writing in English.

I can understand why the company might have shied from any play well-known in the Anglo-American-Australian repertoire, which would have invited a daunting and unfair level of critical comparison. The Trial of Dali ticks some interesting boxes: new, definitely European sensibility at work in it though not of a classical kind, yet fresh, anarchic and American enough to offer something different to an Australian audience.

True to its central character, Trial is in heart and essence a Surreal project. If one asks from it too much logic, too much cohesion, even too much common sense, one is missing its point. The artist comes from New York to be put on trial in his home country of Spain for reasons, and under circumstances, that are never really explained. Andy Warhol and Pablo Picasso, as well as Monroe, make brief and piquant appearances in the proceedings. The trial process itself is a variant of courtroom farce, with hysterical or seductive counsel, a biased judge, and a guard who seems to have strayed in from a Muscle Beach Robot video game.

James Domeyko as Dali is an inspired choice, inhabiting the role given him with physical and linguistic brio. The broader Australian stage awaits him. He and Jola Szewczyk, who brings warmth and sympathy to the part of his wife Gala - interestingly of the older, almost maternal figure - create a convincing portrait of a couple truly bound to each other in every circumstance. All the company of ten are keen and enthusiastic.

The Trial wants to take us into the meaning of Dali, and its methods are not linear and analytic. The courtroom shenanigans and unexplained motivations are best understood as a pretext, the ground for a Bergson’s ‘leap’ apprehension of the artist rather than as a quasi-historical account of him and his path of inspirations.

The performance I saw struck me, in some way, as still a work in progress. The moments of choreographed dance, with stark lighting variations and intense movement were brilliant, completely appropriate to the surrealistic potentials of the play. The music track was amusingly outlandish. The set was studded with Dalian small props, through I’d have liked to see more of his distinctive art projected onto the backdrops - as far, of course, as law and copyright allow.

Some of the cast, understandably, may not have been fully at ease in public performance of their adopted language, with its particular rhythmic cues and rhetorical springs; often they communicated an inhibition, not so much of expression, as of timing. Yet what the text seems to be aspiring towards is a zany, madcap animation, a circumvention of reason that is not necessarily assisted by longueurs or slow takes. A future production might consider, not so much a Pinter or even a Beckett treatment but - to borrow further from the classic cinema which is already in part inspiring it - a little more Marx Brothers pace.

Nonetheless the Artistic Director and the company should be congratulated for tackling this unusual and challenging play. When I look at the wonderful list of modern Polish drama (including works by Zapolska, Perzynski, Przybora, Gronski) that Fantazja has produced over the last sixteen years for their Sydney compatriots, I nurse the hope it might look in that direction again, for a wider audience. Might it mount English-translated versions of some of these, often viscerally political, plays? I am sure Sydney theatre-goers would welcome that, a view into a fascinating world they have heard of yet never seen dramatized.

(c) Copyright JOHN STEPHENSON 2018

Author of The Baker’s Alchemy ( A tale of old Poland)